Not quite dinner table talk: tackling RSE in Muslim homes

Avoiding awkward conversations and eye contact can’t go on much longer.

There is a pressing need to open up avenues of conversations around RSE (relationships and sex education) within Muslim homes.

Society is becoming increasingly lewd and our children are exposed to a plethora of hyper-sexualised content from infancy, putting them at risk of adopting liberal values and a moral code shaped by secular influences.

Research has shown that children in the UK are coming across pornography online from as young as seven years old. While internet safety is a separate – and essential – conversation to be had, appropriate sex education is the compass that will help our children navigate the bombardment of content they will encounter both online and out in the world.

Islam and RSE

As Muslims it is strongly encouraged that sex education be entwined with Islamic principles.

Our moral code is extracted from timeless sources (the Qur’an and Sunnah) and we have existing guidelines on modesty, awrah (parts of the body to conceal), privacy, and more. We have been advised as to when boys and girls should be separated, and to teach children to knock before entering someone’s bedroom. In contrast, secular, liberal RSE wavers on the shaky premise of society’s ever-changing moral code. It is on the basis of whims that mothers decide whether it is acceptable to shower in front of their seven year olds – a real debate taking place in some online circles!

The ‘LGBTQ+’ movement asserts that one has the right to love freely, no desire should be curbed, and feelings can validly form the basis of one’s identity.

Their limits are not grounded in any absolutes, merely shifting with societal norms. As this warped agenda seeps to poison our collective faith, the antidote is to raise children who are firm in their religious identities and guarded by the moral objectivity that Islam provides.

RSE in schools

Statutory guidelines establish core RSE that must be taught in schools, however the resources used for delivery are at the discretion of the institute, shifting an important duty onto parents to find out what materials will be used. The nature of pedagogy is such that the opinions and values of teachers will naturally influence how they teach. The potential harm of this becomes truly apparent with RSE where there is a serious risk of indoctrinating children with beliefs and values that are converse to Islam.

Even if parents choose to opt out of non-statutory RSE classes, countless avenues remain for children to pick up information: from billboards overseeing playground banter to the rainbow-wrapped bus that trundles home where Youtube Ads play.

When parents are the first to teach about delicate topics such as relationships, sexuality, sexual health, and so on, there lies an opportunity to shape the child’s moral code to the mould of Islam and, if bypassed, children’s RSE may come exclusively from non-Muslim, liberal sources. If we don’t answer our children’s questions, offer guidance, and discuss familial and religious values with them, who will?

Parental duty becomes apparent in the following narration: ‘Ibn Umar reported that the Prophet (peace be upon him) said, “All of you are shepherds and each of you is responsible for his flock. A man is the shepherd of the people of his house and he is responsible. A woman is the shepherd of her husband’s house and she is responsible. Each of you is a shepherd and each is responsible for his flock.”

Barriers to conversations

Many parents struggle to have RSE conversations, the most common reasons being:

- Previous generations of parents didn’t talk about it so it’s unfamiliar and uncomfortable

- It is culturally taboo

- It is believed to be immodest and thus contrary to Islam

- They worry that a child’s innocence is robbed of them

- They fear that a child may get ideas and begin to ‘experiment’ early

When modesty is confused with shame parents may avoid anything pertaining to RSE. Whether implicitly or explicitly, everything is branded as immodest or inappropriate. Both avoidance and dismissal of RSE-related topics do a disservice to children; we have a duty to provide children with accurate information rooted in Islamic tradition no matter how uncomfortable it may feel.

Without appropriately explaining the facts of life to children, they may grow up attaching shame to natural bodily processes such as menstruation, desires, and intimacy, possibly resulting in long-term negative consequences (e.g. low self-esteem, body image issues, struggle with marital intimacy etc.).

It is not from religious tradition to avoid sensitive discussions. Aisha (may Allah be pleased with her) said in reference to women asking the Prophet (peace be upon him) about matters of menstruation: “How good are the women of Ansar that their shyness does not prevent them from learning religion.”

Tackling questions & conversations

When we tackle difficult conversations effectively we let our children know they can ask us anything. Some parents bristle at the thought of this, fearing that their child might ask questions about inappropriate or forbidden things. But put it this way – if they don’t feel comfortable asking you they will most likely Google it and the consequences could be disastrous.

Children should feel comfortable approaching at least one parent with any questions and concerns. A child’s curiosity is part of their healthy development and it’s up to us to capitalise on moments when they ask ‘awkward’ questions. The way we respond will shape how comfortable they feel approaching us again – your response to a question from your 6 year old may dictate whether she feels safe asking you about something more serious at 9, and subsequently at 14.

Approaching children with curiosity (“where did you hear that, what do you know about it?”) instead of judgement allows the door to remain open for honest conversations, and provides an insight into their world. Knowing what influences are at play in their lives gives us a chance to step in and offer a grounded perspective while sowing seeds of guidance. When RSE is handled at home with respect and trust children are less likely to go seeking external sources for information or validation.

Tips for answering questions:

- Thank your child for confiding in you so they know they can approach you again.

- You don’t need to answer there and then! Let them know that you’re happy to talk about it with them at a later point (e.g after dinner), and then follow through with it.

- Ask them if they want the long answer or the short answer; sometimes children don’t want a lengthy explanation.

- Engage with them by asking them their thoughts.

Tips for conversations:

There is no fixed age as to when you need to teach RSE. You know your child best – how mature they are, what’s relevant to them right now (e.g. time-sensitive discussions like puberty), and what they might have already learnt from elsewhere. Most of the time, children know a lot more than parents think. You might have to discuss things earlier than you’d like in order for them to hear it from you first.

- Avoid one big sit-down conversation and opt for relevant discussions as and when they crop up (this is known as the drip method).

- Plant seeds of Islamic values repeatedly; children learn best from regular, ongoing reminders.

- Refrain from being judgmental or suspicious of how much they know; instead, be curious so you can get a better understanding.

- Focus on what is permissible and positive rather than honing in on things that are forbidden and immoral.

- Model behaviours regarding privacy, modesty, intermingling etc.

- Encourage open discussions about everyday behaviours (such as donning modest attire before leaving home) so as to help children form connections between actions and values.

Example scenarios

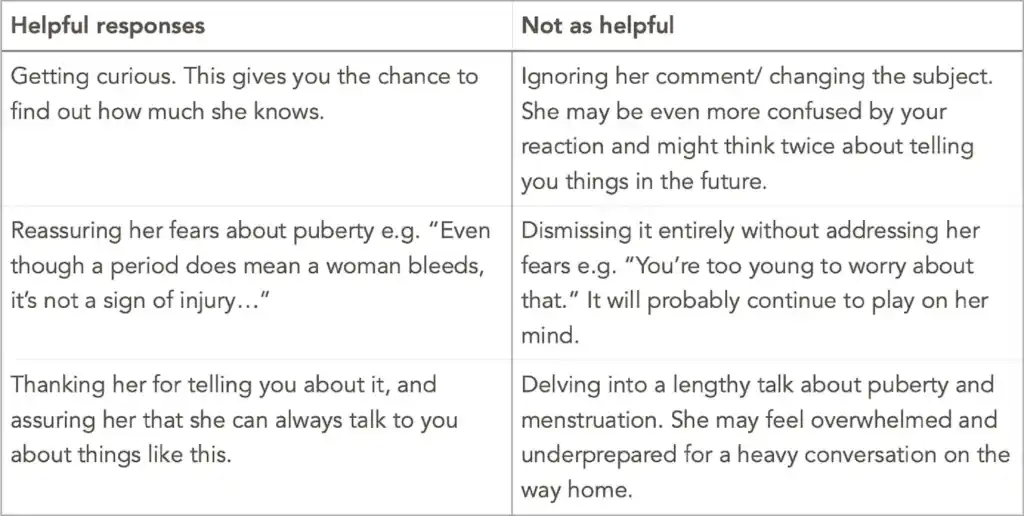

Scenario 1:

As you walk home from school your six year old daughter says, “Mummy, my friend Sadia said her sister started her period on the weekend. She said her sister started bleeding!” Your daughter hasn’t asked you a question yet she is clearly confused and frightened about what she’s heard, and in the midst of playground gossip she may have picked up some false information

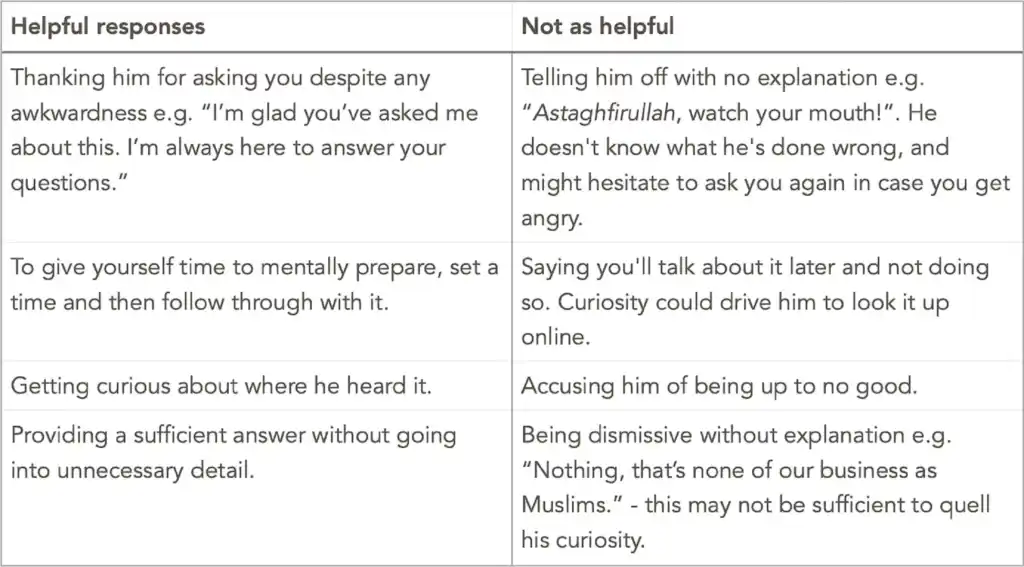

Scenario 2:

As you work in the garden with your nine year old son, he tells you he recently heard the word ‘porn’ and wants to know what it means. You feel mortified and like you’ve been put on the spot

Newsletter

© Copyright 2024 – Muslim Family Initiative